Associated Press

May 15, 2006

http://hosted.ap.org/dynamic/stories/I/IMMIGRATION_EDUCATION?SITE=AZPHG&SECTION=HOME

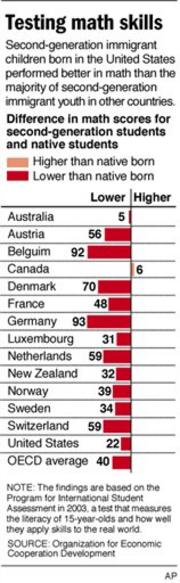

WASHINGTON (AP) -- Immigrant 15-year-olds in the United States don't do as well in math, reading or science as native-born children, and many have only basic skills, a study finds. But immigrants aren't as far behind in the U.S. as they are in some other major nations.

The findings are based on the Program for International Student Assessment, a test that measures the literacy of 15-year-olds and how well they apply skills to the real world. It is given to students in many industrialized countries and considered an international benchmark.

In the United States, first-generation immigrants, who were born outside the country just like their parents, are almost a year behind in math.

Second-generation immigrant kids - who were born in the United States but whose parents were not - are about a half-year behind, a smaller deficit.

Similar but slightly larger performance gaps exist in reading and science, according to an analysis released Monday of how immigrants performed on the most recent test in 2003.

A troubling number of immigrant children are at the bottom end of the achievement scale, which has implications for their work life and integration into society. By age 15, students have typically reached grade nine or 10 and are nearing the end of mandatory schooling.

For example, in math, at least three in 10 U.S. immigrant students have only the most basic skills. That means they often cannot apply math concepts to everyday situations.

On the positive side, immigrant students, particularly those who started their schooling outside the U.S., report high levels of interest in core subjects and in school generally.

"They want to learn," said Gayle Christensen, co-author of the study and a research associate at the Urban Institute. "They're excited about going to school. They have high expectations for themselves. Now the next step is, how can we make sure that they realize those expectations for themselves? That's where the gap is."

The language of home life makes a big difference. U.S. immigrants did just as well in math as native-born children when English - the language of instruction at school - was spoken regularly at home. When it wasn't, immigrants did significantly worse.

Countries with smaller learning gaps between immigrants and native students tend to have well-established language support programs with clear goals and standards, the study found.

The review covered 17 nations. Fourteen are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a coalition of industrialized nations that runs the test. Three partner countries also took part: the Russian Federation, Hong Kong-China and Macao-China.

The United States fared favorably compared with Germany, France and other nations in terms of the academic performance of immigrants. Australia and Canada posted better marks.

Immigration has become a dominant issue for Congress and for President Bush, as lawmakers try to tighten the country's borders but also improve the paths to citizenship and work. Immigrants and their supporters have staged rallies and boycotts to demand fair treatment.

An estimated 53 percent of U.S. immigrants come from Latin America; 25 percent are from Asia, 14 percent from Europe and 8 percent from other areas, according to the Census Bureau.

--

On The Net:

Program for International Student Assessment: http://www.pisa.oecd.org